U.S. Air Force Master Sgt. Jeremy S. Fraser, 71st Special Operations Squadron noncommissioned officer of training, flies on a CV-22 Osprey during a training exercise near Albuquerque, New Mexico, May 27, 2021. During the exercise, the crew surveyed and landed at three new landing zones that Kirtland Air Force Base will use to conduct future training operations to ensure mission readiness. (U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Ireland Summers)

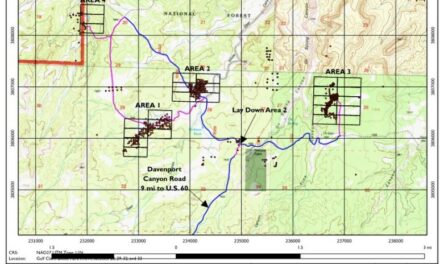

About 20 times a year, Air Force Master Sgt. Eric Denman will take off from Kirtland Air Force Base in a CV-22 Osprey and fly south to the Magdalena Ranger District of Cibola National Forest.

As quickly as 20 minutes after takeoff, Denman and other airmen, often those training under his guidance, find what they’re looking for: Difficult flying conditions.

Landing zones in the area are at altitudes between 5,500 and 6,500 feet above sea level, which creates struggles for pilots because of the thin air. In the summer, temperatures often soar above 100 degrees, further complicating flight dynamics. Plus there’s fine dust everywhere and it quickly envelops the craft and chokes the engines, requiring the pilots to rely on instruments instead of their eyes as they try to land.

In the winter, Air Force crews fly to the forest at night in freezing temperatures, and it’s so dark and isolated their night vision equipment isn’t enough to navigate the terrain.

Denman compared flying in the Magdalena to flying in “Middle East locations.”

“Every deployment I’ve been on, it’s not a shock to get there and have to operate in those areas because of the training we’ve gotten here,” he said. “Without having that (training area), there would be a learning curve when we get to those high-altitude, high-temperature environments.”

Public lands around Albuquerque will remain a proxy for the Middle East for years to come.

The Air Force and the Cibola National Forest recently completed a permit that allows the service to train on national forest lands outside Albuquerque for the next two decades.

The two federal agencies signed the permit after a roughly 10-year process, which included scoping – an official process to examine how the training would affect the local community and environment – and public comment periods. Objection letters were filed by nearby landowners and conservation advocacy organizations, and environmental assessments were completed.

The permit will expire at midnight on Dec. 31, 2041.

Over 40 years of training in forest

The permit applies to two groups at Kirtland Air Force Base: The 351st Special Warfare Training Squadron, which uses the lands for mountain rescue training, land navigation and other tactics, and the 58th Special Operations Wing, which trains more than 1,000 airmen per month in several aircraft, including the CV-22, a unique-looking tilt-rotor aircraft that combines a helicopter’s ability to hover and land with the speed and fuel efficiency of a turbo-prop plane.

The aircraft’s mission is long-range infiltration and exfiltration of special operations forces, and much of that training takes place in the Magdalena Ranger District west of Socorro.

The latest permit allows the 58th SOW to create three more landing zones in the area, which will add to the difficulty of landing there because now the airmen will have to navigate different obstacles, said Col. Michael Curry, the commander of the 58th SOW.

The 58th SOW also uses the national forest for C-130 drop zones. And the U.S. Marine Corps 4th Reconnaissance Battalion has traditionally trained in the national forest.

On Thursday, the training wing for the first time used the landing zones created by the new permit. The permit gives the Air Force access to over 70,000 acres of national forest land for training exercises. Different types of training can happen in four of the Cibola’s ranger districts: Mount Taylor, Magdalena, Mountainair and Sandia.

Military training in Cibola National Forest dates to 1977, when the Forest Service gave the Air Force its first special use permit.

The public scoping period for the newest permit started in January 2010, according to Forest Service documents.

A draft environmental assessment was released in 2013, which was followed by a public comment period and public meetings.

‘We lost the battle’

There was opposition to the military training, which is one of the reasons the permitting process took a decade.

Patricia Johnson, a spokeswoman for Cibola National Forest, said in an email that the Forest Service added extra time for public comments during the process.

The Forest Service received about 185 comments, which led to two objection resolution meetings. Those meetings happened in August, and letters have been sent to the objectors, she said.

New Mexico Wild, Backcountry Horsemen of New Mexico, the Sierra Club, New Mexico Sportsmen and The Wilderness Society were among the groups that asked the Forest Service to consider alternatives to using forest lands for military training. Their requests included limiting military training to military lands, according to Journal archives and permitting documents.

Logan Glasenapp, a staff attorney for New Mexico Wild, said the organization raised concerns that the military training has affected vegetation near landing zones, affected wildlife and increased traffic in the area.

“At the end of the day, in the back of our minds is a concern that our public lands may start to resemble war zones,” he said.

Several people who live near the training sites also opposed the permit, including Arian Pregenzer, a retired physicist who worked at Sandia National Laboratories.

“We lost,” she said. “We lost the battle.”

In 1996, Pregenzer bought 160 acres near Magdalena and built a rammed earth home.

“It was basically a place to get away and have solitude,” she said.

But her home is within sight of the current helicopter landing zone in the Magdalena Ranger District.

She said she’ll also be able to see two of the three new landing zones.

Day and night, when the CV-22s come in for landing, she said, the walls of her house shake and the windows rattle.

“Up and down, up and down, up and down. Thenthey make a circle and come back,” she said, describing

the training exercises. Pregenzer was one of several Magdalena-area residents who argued thatthe training on forest land is unnecessary.

“I worked with the military. I have a lot of respect for them. But they need to be questioned. And they need to be held to account,” she said. “Why can’t you (train) at Kirtland? or White Sands? We have 5,000 square miles of military land in New Mexico, why can’t they do it there?”

Johnson said that the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Defense have entered agreements that allow for such military training on national forest lands.

“National Forests are managed for multiple uses,” Johnson said. “To sustain mission readiness, the military needs to train under a variety of conditions and landscapes. Desert, mountainous and forested terrain are all found within the Cibola National Forest and National Grasslands.”

Privilege to train Curry said the training offered in nearby national forest lands is invaluable.

“It makes for the most challenging flying we’re going to do,” he said. “I want them to experience those difficulties here so when they are challenged on the operational side, the flying part becomes less challenging.”

Denman said the Air Force personnel who use the training areas understand it’s a privilege. He said all instructors and students in the 58th SOW are required to read the requirements set in the permit.

And he says the Air Force does all it can to mitigate noise and other effects in the area during training exercises.

The operating plan for the permit places numerous restrictions on the training exercises. For example, all sessions are capped at 40 students and 15 instructors. No pyrotechnics or blank ammunition can be used during times of high or extreme fire danger. The military has to clean up after its exercises each day.

There are also more specific restrictions. For example, the Air Force can’t fly within 1 mile horizontally or 1,000 feet vertically of any known golden eagle nesting sites from February through August. The Air Force also isn’t supposed to intentionally fly low over livestock, wildlife or dwellings, according to the operating plan.

“We have to be respectful. Using the LZs (landing zones), it’s a privilege for us to be out and use this place,” Denman said. “It’s not something we’re entitled to. And that being the case, we have to take care of it.”