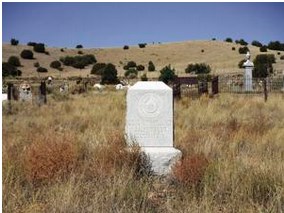

Claude and Ginger Hudspeth at his granduncle Henry Coleman’s gravesite John Larson | El Defensor Chieftain

Claude Hudspeth of San Angelo, Texas, got it in his head 20 years ago that he needed to track down the burial place of his grandfather’s brother – his granduncle – who was a controversial figure in the history of Socorro County ranching. That search brought him to Magdalena and Henry Coleman’s final resting place.

It was in the Magdalena cemetery he found a gravesite headed by two barely readable concrete markers that read, HENRY COLEMAN, DIED OCTOBER 15, 1921.

“There were a lot of killings going on then. Especially this area right here in New Mexico,”

Claude said. “Henry Coleman was my granddad’s brother, Henry Hudspeth. He changed his name to protect the Hudspeth name. There was talk of him being an outlaw, and I wanted to find out if it was true or not.”

Claude persisted and began collecting a little more information on his granduncle.

“Jerry Don Thompson, a professor emeritus at Texas A&M in Laredo had done some research,” he said. “He called me up and wanted to know if I wanted to talk about it. I said yeah I’d love to talk about it.

“I got more interested coming up here,” Claude said.

His research showed that Coleman met his demise a few miles north of Quemado when a small band of vigilantes bushwhacked him for what they claimed was stealing their cows. But the story of Coleman may be a little more complicated.

“He always wore a pistol, even then,” Claude said. “He told someone, that’s the only protection I have … is that pistol. You know what I mean.”

Some say he was guilty of numerous crimes and misdemeanors. Others thought he was an honest rancher.

“Some people hated him. And others loved him,” Claude said of his relative. “I’m not sure which side is true, but since he was my grandfather’s brother, I’ve got a fourth of him in me.”

On the other hand, one of his brothers was a U.S. Senator, another, a very prominent attorney, and a Texas County bears the Hudspeth name.

“All the books and have read everything he was a roughneck,” he said. “He did kill some people. But, at that time, it was still the wild west out here. Cattle were running on the BLM land. There were cows and calves that didn’t have a brand on it, so they’d go ahead and put a brand on it. That kind of thing.”

There are at least three accounts of Henry Coleman’s life and death. One published in the Reserve newspaper, another published in True West Magazine in 1982 and one version found at the New Mexico State Records Center and Archives in Santa Fe.

While in his early 20’s Henry Coleman left Texas and relocated to New Mexico near the Mexican. It was in and around Deming where he first became notorious, keeping company with three others who started by buying cheap cattle south of the border. However, the profits were small, so he and his friends startled rustling stock.

According to the archives in Santa Fe, one day Coleman, accompanied by one of his men, went to Silver City to get some checks cashed, when he encountered four men from whom he had previously stolen cattle. They accused Coleman of stealing their cattle and guns were drawn. Coleman killed two of them, wounded two others, and made his getaway. From then on he became unpopular, and it is said he confined himself to the theft of Old Mexico cattle.

In 1915 he married a woman named Clara Oliver, who with her young brother, Don Oliver. moved to a ranch on the Canyon Largo in New Mexico.

Returning to the Canyon Largo ranch after the delivery of a bunch of stolen cattle, Coleman found that his wife and her brother had been murdered in her home.

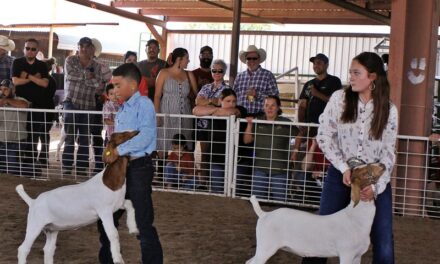

Don Oliver

The grave of Don Oliver, who was murdered at the same time as Henry Coleman’s wife, Clara, in December, 1918.

The grave of Don Oliver, who was murdered at the same time as Henry Coleman’s wife, Clara, in December, 1918.

“We found where the house was,” Claude said. “The only thing left is the chimney now. She’s buried in the Catholic cemetery in Quemado.”

Suspicion fell upon Coleman, but he had no difficulty in establishing an alibi. Suspicion then fell on a man named Bourbonaisse, a neighbor of Coleman’s living some six miles from the Largo ranch.

The sheriff and his deputies arrested Bourbonnaise, and the same night stopped at Coleman’s ranch for supper while on their way to Socorro with their prisoner. The four men were told to get down and come into the house. Bourbonnaise was the last to enter, and as he entered the door Coleman shot him dead.

“All the movies you see, people just think, aww, it’s just a western. But it’s history,” Claude said. “They aren’t making this stuff up.”

Coleman claimed he shot in self defense and managed to beat the case.

By October, 1921, reports were coming into the DA’s office of cattle stealing by Coleman and an accomplice. Coleman was out on bond on another case, and when he didn’t show up for court a warrant for his arrest was issued.

The sheriff deputized three men to form a posse and found Coleman at what was called the Old Goat Ranch, southwest of Salt Lake in the western part of what’s now Catron County. As the posse saw Coleman, they began shooting. Coleman’s horse began bucking. He into an arroyo and never had a chance to draw his gun. During the shooting, a bullet entered Coleman’s leg and cut an artery. He lay out all night and bled to death.

Coleman’s death made the front page of the Reserve Advocate newspaper the following week. It reported that “just about sun-up Coleman came on horseback towards the posse and that immediately upon the attempt to make the arrest, the gunfight started, which resulted in the death of Henry Coleman.” District Attorney Fred Nicholas stated in the article that he found nothing in his investigation to indicate that the affair was anything but a justifiable killing.

Coleman was subsequently buried at Magdalena.

Two weeks ago, Claude and his wife, Ginger, along with Mayor Richard Rumpf, oversaw the installation of a more prominent headstone on his grave.

“He was a nice fellow, educated man, but he had a streak,” Ginger Hudspeth said over Colemans’ grave. “And it got the better of him.”

Don Oliver is buried in the Magdalena cemetery just a few feet from Henry’s grave.