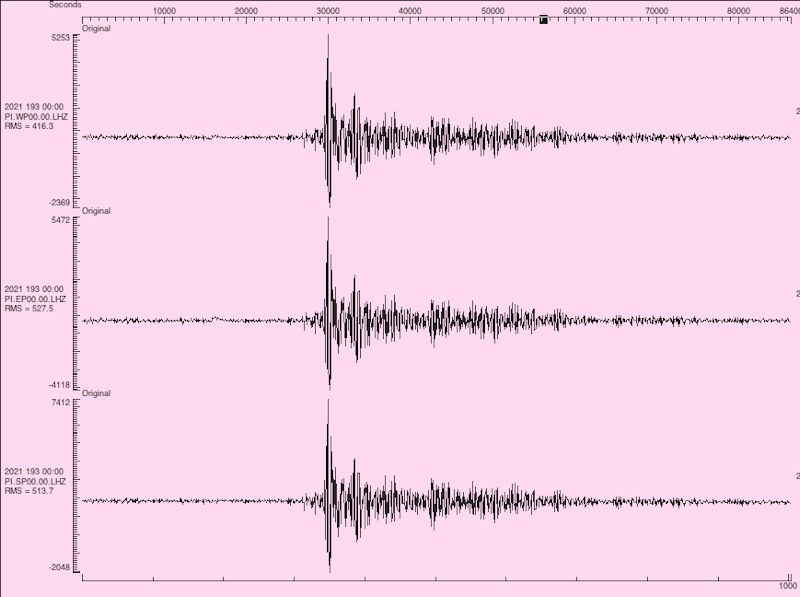

The seismograph readout at PASSCAL shows the earthquake S-wave from the Valles Caldera

area reaching Socorro – over 120 miles distant – in 27 seconds.

Courtesy of Dave Thomas, IRIS PASSCAL

The earthquake that rattled windows in various Northern New Mexico communities last week was a reminder that the state of New Mexico is still a seismically active place.

Although the earthquake that occurred near Capulin – west of Abiquiu – was a magnitude of 4.2, it was felt as far away as communities in Santa Fe and Los Alamos Counties.

In Socorro, the movement was picked up by sensors at IRIS/PASSCAL at New Mexico Tech.

According to Dave Thomas, staff physicist at PASSCAL, the tremblor took 27 seconds to reach the facility’s earthquake sensors.

He said the sensors picked up the 4.2-magnitude quake at 9:33:35 a.m. on July 12.

“There were some weaker quakes – magnitude 3.0 at 7:44 a.m. and magnitude 3.7 at 10:06 a.m., but these don’t show up that clearly,” he said. “These measurements are made on our ‘piers,’ solid slabs of concrete with sensors on them running 24/7.”

IRIS/PASSCAL is the facility that provides instrumentation for the National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, and other funded seismological experiments around the world. From Alaska to Antarctica to the outer reaches of Inner Mongolia, instruments shipped from PASSCAL can be found measuring earth-shaking events virtually all over the world.

“Some sensors here at PASSCAL are used to constantly measure earthquakes worldwide, and are sensitive enough to record train passages, nearby trucks and cars, and even the 4th of July Fireworks celebration,” Thomas said in a 2018 interview.

Seismometers at IRIS PASSCAL

JOhn Larson | El Defensor Chieftain

PASSCAL currently maintains multiple seismometers in its facility that can register earthquakes anywhere in the world.

“The 2016 Alaska earthquake near Anchorage was a 7.1 magnitude, and took eight minutes to be registered on the seismographs here at PASSCAL,” Thomas said. “That was 2,700 miles away.”

That means the shockwave was traveling 20,000 miles an hour through the earth.

To illustrate the sensitivity of PASSCAL’s instruments, Thomas remarked that trains passing through also register on the seismographs’ waveforms with a time stamp.

“We can tell if the trains are running on time,” he said.

Although New Mexico, geologically known to have had many volcanoes in the distant past, the chance of a large earthquake is minimal. Residents in the Socorro and middle Rio Grande region periodically experience earthquakes no stronger than in the two to three points on the Richter magnitude scale.

However, a magnitude 6.0 quake in 1906, did cause structural damage in Socorro.

A New York Times account of the event in July of that year said “…practically two-thirds of the town is falling down. The Court House is in ruins and the people of the town are in terror. The railroad service has been crippled … ”

That account was strongly criticized in the very next issue of the New York Times by then-mayor Holm Bursum. “The reports regarding the earthquake at Socorro have been exaggerated,” Bursum wrote. “The damage to date being limited to the falling and toppling over of loose chimneys and shaking of some of the walls of buildings not of substantial character.”

An account published by geophysicist Harry Fielding Reid was more detailed.

“Between July 2, 1906, until well into the year of 1907 scarcely a day passed that slight shocks or tremors were not felt at Socorro … and in its vicinity; and shocks severe enough to do some damage occurred on July 12 and 16, and on November 15. The series was inaugurated by smart shocks at 3:15 and 3:30 a.m. on July 2, felt probably everywhere within 50 miles of Socorro.”

Fielding writes that the first severe shock came at 5:15 a.m. which lasted from fifteen to twenty seconds.

“The walls of many adobe houses were cracked and some brick chimneys were thrown down. Many boulders were shaken down upon the branch railroad to Magdalena a few miles west of Socorro, breaking one rail and a number of ties,” Fielding wrote.

Over at Tech’s Earth and Environmental Science Department, Chair Susan Bilek, Professor of Geophysics says research into the history of quakes in the region is ongoing.

“My graduate students and I have been working on trying to improve our knowledge of what earthquakes have happened in the past in this area,” Bilek said. “We’re taking a lot of the data that have been collected over several decades of seismic monitoring in this part of the state and trying to employ some new techniques – machine learning, computer learning techniques – to try to identify other little earthquakes in that date we may have missed. And then locate where they happened and then try to see if they’re happening on certain faults that have been mapped in the area.”

Records at New Mexico Tech show that the Socorro region generally averages six earthquakes a year with a magnitude of no greater than 2.0.

Associated with local seismic activity is the Rio Grande Rift – running from the Jemez Mountains down through the state – caused by a stretching of the crust, rather than a pushing together of plates. Related to the rift is the Socorro Magma Body lying 12 miles below Socorro and Lemitar. The pancake-shaped “blister” is slowly inflating and stressing the rocks above it, causing the ground above it to rise one to two millimeters a year.

This rising, researchers say, causes shallow earthquakes, generally in the 1.0 or 2.0 magnitude range.

PASSCAL is an arm of IRIS, as is the EarthScope USArray Array Operations Facility (AOF), which also operates out of the same building. The combined PASSCAL Instrument Center and AOF currently support a total of 33 professional New Mexico Tech staff, as well as a contingent of student workers.