Civil War reenactors bring the history of a clash between Union and Confederate troops in

Socorro County to life every year.

John Larson | El Defensor Chieftain photos

The year was 1862. The mining boom which would bring prosperity to Socorro would not start for another handful of years, and in the early 1860s, Socorro was little more than mostly adobe homes and buildings with a population of about a thousand.

The Civil War was heating up back east and would soon come to New Mexico. At that time, Socorro County extended from Texas to California, and the Confederates hoped to capture the Southwest, including New Mexico, the gold fields of Colorado, and all the way to the California coast.

This Saturday and Sunday, Feb. 18-19, dozens of Civil War re-enactors will turn back the clock as Confederate soldiers attack New Mexico’s Union volunteers in the 23rd annual Battle for Socorro. The event, held on the banks of the Rio Grande at the Escondida Bridge, commemorates New Mexico’s early involvement in the War Between the States, a brief but important period of the Confederate Army’s attempt to control the Southwest.

Organizer Gabriel Peterman said he expects over 50 reenactors to take part.

“We have re-enactors coming in from all over the state,” he said. “We’ll have, of course, infantry, cavalry on the Confederate side. On the Union side, we’ll have artillery and infantry.

“On Saturday, the Union troops will hold the fort that’s near the bridge, and then on Sunday we’ll flip the scripts and let the Confederates have a turn at defending the redoubt,” Peterman said. “All our reenactors utilize either original or period-correct reproductions of the firearms. They’re usually 58 to 69 caliber muskets.”

Peterman said there are strict standard safety procedures prior to each faux battle.

“Every musket is inspected beforehand. No ammunition is allowed on site. That’s our standard operating policy,” he said. “If we found a round of actual ammunition, you are banned. And it’s a lifetime ban, where you’re not allowed back on the field, ever.”

The muskets use black powder, and Peterman said it takes a lot of work to load it, especially when the use of a live round is involved.

“You have to get a cartridge out of the cartridge box. You have to rip the powder bag open and pour the powder down the barrel,” he said. “Then you have to grease the bullet, put it in the muzzle and then pull out your ramrod and literally beat the bullet down the barrel. Once you get it seated all the way down, then you have to put a percussion cap on what is called the nipple of the rifle, and then manually cock and fire.”

Reenactors use a simpler method since no lived rounds are used.

“We simply pour the powder down the barrel and maybe pump it on the ground to seat it pretty good,” Peterman said. “So, when you talk about firearm safety during reenactments, we don’t even allow the participants to draw ramrods. Another reason is to avoid the off-chance that someone would leave it in the barrel, and it would become a projectile.”

The procedure for the cannons is similar; no rounds, only smoke coming from the muzzle.

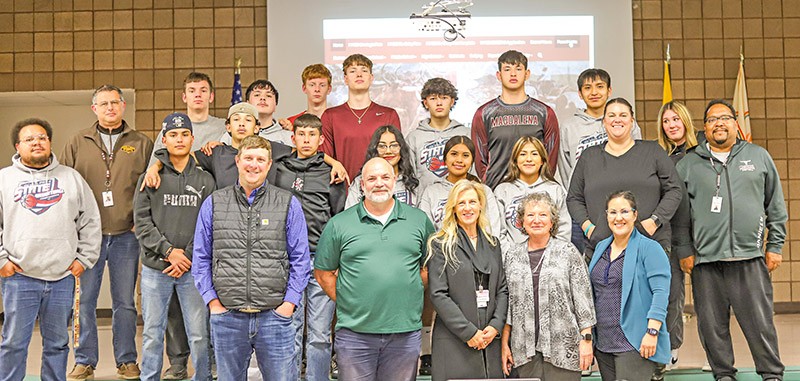

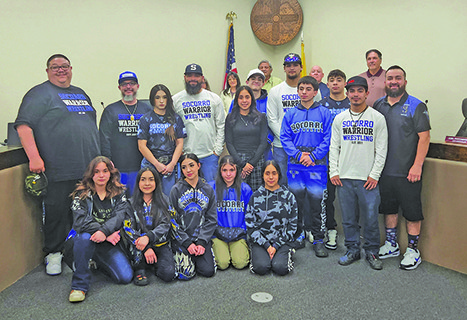

Union troops defend the redoubt at Escondida.

The reenactment schedule will be abbreviated from years past.

The battle presentations will be Saturday at 10:30 a.m. and Sunday at 11 a.m. The Union and Confederate encampments will be open to the public right after the battles.

“We encourage everyone to come into the camps,” Peterman said. “It’s really an interesting aspect of life. It’s almost more interesting than the battle, to see how they actually sustain themselves in the field.

“Unfortunately, we will not be having the fandango, the dance, this year,” Peterman said. “The person normally organizing the dance passed away.”

In 1862 Socorro County extended all the way from Texas to California, and the Confederates hoped to capture the entire region.

Confederate Gen. Henry Hopkins Sibley planned to invade New Mexico, defeat Union forces, capture Santa Fe, and then march westward to conquer California and add the territory to the Confederacy. His first step was to gather an army in El Paso to capture Fort Craig.

On Feb. 16, 1862, the Confederate 5th Regiment of Texas Mounted Volunteers formed a battle line and headed for Fort Craig, garrisoned south of Socorro eight years before protecting settlers and homesteaders from Apache raids. The Union army’s Col. Edward Canby stationed a battery of guns and howitzers outside the south-facing walls of Fort Craig. Seeing this, the Confederates then called off the attack and withdrew.

Three days later the Confederates moved north to control the ford on the Rio Grande at the town of Valverde, driving the Union soldiers back to Fort Craig to meet them. The next day the two armies clashed near the river.

The Battle of Valverde ended in a tactical victory for the Confederacy, but Sibley’s forces failed to capture Fort Craig.

After breaking camp two days later, the Confederate 5th Texas Mounted Rifles easily defeated the Union’s 2nd New Mexico Militia stationed in Socorro.

The capture of Albuquerque and Santa Fe followed. But Confederate forces lost steam after losing a battle at Glorieta Pass, southeast of Santa Fe, so Sibley decided to take his Confederate troops back to Texas on a roundabout route. Worn out and short on supplies and ammunition, Sibley’s army veered west at Ladron and then south in order to pass between the Magdalena and San Mateo mountain ranges to avoid getting too close to Fort Craig. They buried some of their equipment in the Bernardo area before passing on the north side of Ladron.

Visitors can learn what life was like behind the front lines.

Confederate uniform buttons and other artifacts have been discovered along that route, specifically in the area of Pueblo Springs, north of Magdalena.

Peterman said he hopes the annual event attracts more interest in Socorro’s diverse history.

“One of our goals is to try to expand their living history, beyond the Civil War re-enactment,” Peterman said.

Peterman, a Major in the New Mexico National Guard, has been involved with reenactments for about 18 years and holds a master’s degree in history from New Mexico State University.

“One of my great-great-great-grandfathers was an officer in the 17th United States Colored Infantry during the Petersburg Campaign,” Peterman said. “It was one of the first Black regiments in the U.S. Army, and he was one of the officers who volunteered to go ahead and work with them, knowing full well that if the Confederates caught him he would’ve been executed for leading African Americans.”

The encampment on the north side of the Escondida Bridge opens to the public Saturday morning after the battles are performed both on Saturday and Sunday.