The Belen group had to drill into granite to install the plaque, not an easy task. They brought a bucket of water to cool the drill bits. Mickey Cone | Courtesy

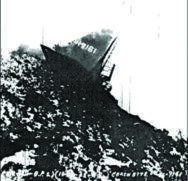

In 1942, a B-17 crashed into North Baldy Peak near Magdalena during a routine training exercise.

Nine men were killed, but the crash was not publicized during the time. A group of friends from Belen was determined to mark the crash site in an effort to preserve this history for future generations.

They made the hazardous climb to the crash site on Oct. 15, the 80th anniversary of the tragedy, to install a bronze plaque.

Several of the men wanted to commemorate the 80th anniversary because they are also 80 years old.

The youngest member of the team was 49.

History of the Flight

Obtaining credible information on the tragedy is difficult, because the Wartime Act prevented newspapers from printing stories of domestic military accidents, according to a 2007 Chieftain story on the history of the crash written by local historian Paul Harden. He used military records to piece together what happened that night.

Many B-17 crews were trained in the Southwest during World War II, according to Harden’s story, and in 1942, Alamogordo was the main training base for the 330th Combat Group, 459th Bomber Squadron.

The crew who died in the crash are: pilot 2nd Lt. John R. Pratt, co-pilot 2nd Lt. Donald F. Jackson, navigator 2nd Lt. Lawrence W. VanTassel, bombardier 2nd Lt. Joseph L. Grant, engineer Sgt. Hanson E. Ortmyer, assistant engineer Sgt. Robert C. Myers, radio operator Staff Sgt. Thomas C. Ferron, assistant radio operator Sgt. William G. Walls, gunner Sgt. Dale A. Rottier.

This history marker was installed at the site of the B-17 41-9161 plane crash on the 80th anniversary of the tragedy. Mickey Cone | Courtesy

Pratt had 368 flight hours, with 86 hours on the B-17 before his final flight. Co-pilot Jackson had 294 flight hours. The crew was almost ready to be transferred to the combat squadron, Harden writes.

On Oct. 15, 1942, Pratt and his crew set out on a training mission. They completed mission targets near Carrizozo, Vaughn and Albuquerque before making a “bombing run” on the airstrip northeast of Magdalena.

“Most everyone in Magdalena that night remembers well the B-17 as it circled the town. For many, it woke them up,” wrote Harden. “There is no doubt of this. A B-17 flying over your house at 700 feet would probably rattle the fillings loose in your teeth! For Magdalenians, it must have been quite a sight (and sound).

“Most witnesses also remember hearing the plane, after circling Magdalena, head to the southeast toward the mountains, with a change in the sound of the engines as they worked to gain altitude. Many had an immediate feeling that there was no way the plane was going to clear the Magdalena Mountains.”

The plane collided with North Baldy about 75 feet from the summit, which is at 9,858 feet. Harden writes that the Army may have had an incorrect understanding of the summit, as archived accident reports consistently cite the elevation at 9,500 feet.

No evidence of sabotage or engine malfunction was found, and the final report summary attributes the cause to a misjudged altitude or location of the peak.

Magdalena was removed from future B-17 missions in New Mexico.

One of the photos (microfilm) of the Magdalena crash from the official U.S. Air Force accident report, clearly showing the “41-9161” tail number (”41” indicates the year of manufacture). This Oct. 18, 1942 photo shows the crash site less than 100 feet from the summit. Courtesy Army Air Force microfilm archives

Remembering the Story

Memorials cannot be placed on National Forest land, but history markers can, and Belen resident Mickey Cone was determined to ensure this piece of history is not forgotten.

Cone first heard rumors of the crash in 2019, and with a little research, he found Harden’s story. In October 2020, Cone visited the crash site for the first time to do metal detecting. Although little of the plane remains, Cone found a push rod cover off the engine.

“We get back and the interest kept getting stronger or gnawing on me, because there’s hikers up there and they don’t know the history,” said Cone.

He recruited a team of neighbors in Belen. The group pitched in to purchase a bronze plaque that could be placed at the crash site, but with delays meeting up with each other, it took another year before seven of them could make the trek up and place the plaque.

“I think why it grabbed me so much is because that was the year I was born. I’m 80 years old. It happened about a month and a half after I was born.”

The road from Kelley up to North Baldy is rough, even for a jeep. Cone had not one, but two tires get their sidewalls cut, and the group had to keep stopping to move rocks out of the path of their vehicles. Fortunately, he planned for that possibility, and brought not one, but two spares.

After the drive, there is a hike from the parking spot to the crash site. Armed with drills and a gallon of water to cool the drill bits, the team was ready for the climb.

“In January, I had surgery, and they removed part of my lower right lung and then I had chemo after that, so it was a hard climb for me,” said Cone.

Cone’s wife, Virginia, couldn’t make it to the top, but appreciated the views from the parking area. Cone took a tumble on his way to the site, slipping on the shale, and leaving him with scrapes on his forehead, hand, arm and knee.

“When I fell, I hit my head, my glasses fell off, both hearing aids went out. I found one. I called Cintos to come back down and help me, and with his metal detector he found my other hearing aid. So that saved me quite a bit of money.”

B-17 Connection

One team member, 80-year-old Bill Britton, felt a special connection to the project because of the aircraft. His father, Benjamin Alexis Britton, died in a B-17 training crash during WWII. Britton’s father left for war before he was born.

“My father died training others to get ready for the war, because in those days they separated the crews that were trained so that they could bring more on board and get hands-on experience, before the real event,” said Britton. “They made a mistake. They were low on fuel and turned back to refuel and that’s when they made a mistake flying over enemy territory and were shot down.”

Britton became emotional at the top of the hill when they finished installing the plaque.

“No one knew. It was just something I had in myself for myself. I was just grateful that I was in the shape that I am and able to still do that in memory of him. We had some moments of silence. These gentlemen had some beautiful moments of prayer. It’s meaningful to me, and I’m grateful to those men who sacrificed in life in training to protect our country.”

Someday, Britton may visit his father’s plane crash site in France.