Granted, we have a handful of days set aside each year to recognize our military in one way or another, but Memorial Day is expressly set aside to honor those who died serving their country. Most lost their lives on the front lines and in combat zones, but not all.

Chieftain editor Cathy outlined the details of one such instance in an article back in October. A group from Belen placed a memorial plaque on North Baldy honoring the members of a B-17 crew who died in a training accident in 1942.

If I may revisit the story, it was a Saturday morning over coffee back in 2006 that I first heard about the crash. It was from the late Water Canyon rancher Tom Kelly, a teenager at the time and one of the first to reach the crash site. When I asked him if any of the wreckage was still up there, he said, “I don’t think so, but I can show you where it was.”

After the coffee cups were drained, we piled into his pickup, and on the way up, he told me what he remembered of the crash and how he assisted the Army in the recovery of the bodies.

As recounted in Cathy’s article, the crew was on a training mission out of Alamogordo, flying over the Magdalena flats, practicing bombing runs using the new top secret Norden bombsight.

Tom said he had just come out of the Silver Bell Saloon from shooting pool with his pal Skinny Knoblock that foggy October evening and noticed the B-17 flying “real low and he had his lights on, making a lot of noise. It went right over town, and I said something like, ‘he better get up there or he’s going to hit something.'”

A moment later, there was “a big flash of red flame up there. You couldn’t see anything ‘cause it was foggy,” he said. “All you saw was a big glow.”

The next morning, the then 17-year-old Tom saddled up at their Water Canyon ranch with “my dad, Frank Kelly, Jim Kelly, that’s my dad’s brother, and his son, my cousin J.B. Jr., and there was Dutch Knoblock, Fleck Danley, and Skinny Knoblock, he came too.

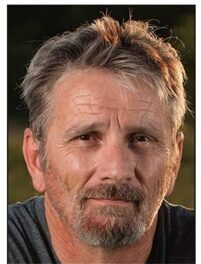

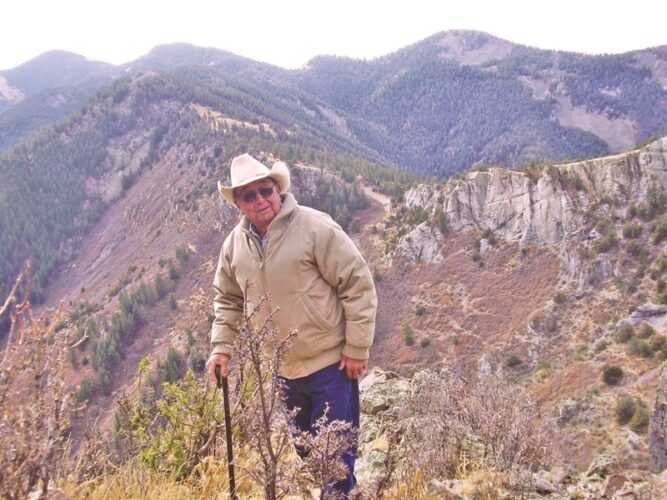

The late Tom Kelly returned to the B-17 crash site on the south slope of North Baldy in 2006, recalling how he and other cowboys assisted the Army in recovering the bodies of the crew in 1942.

John Larson | El Defensor Chieftain photos

“We rode up there, and when we got there, it was about 10 degrees above zero, and everything was frozen. It was snowing,” he said. “It was also snowing a little bit when the plane hit. It was colder than heck.”

Since they were on horseback, they were the first on the scene that first day, and coming up behind was a contingent of GIs in jeeps and ambulances, which only could get to within two miles from the top, he said. “We got up on top where the crash was and there wasn’t anything burning. It had all gone out. Anyway, the plane had hit on [the Magdalena] side of Little Baldy between 60 and 100 feet from the top. It dug a big hole where it hit.”

When Tom and I finally reached the top, he was finishing his story. Standing in the same spot he stood as a teenager in 1942, Tom pointed to the hillside where the crash happened. “The wings of the plane were burned but not completely, and there were pieces of metal lying there,” he said. “The aluminum had melted, and it had run off the hill just like water from the fire.”

Four burned bodies were in the plane, “which we figured was the pilot, co-pilot, the bombardier, and the navigator because they’re up in front.”

When it hit, the tail slapped the ground and broke the plane in two, but the tail was intact, Tom said. “When he hit, he scooted right up the hill over the top and down the other side, a couple of thousand yards, and there’s a bluff down there, a flat spot, and he came to rest right on that rock, and that’s where it burned.”

The tail gunner was still in the tail, and it looked like nothing was wrong with him. He was just laying there, but he’s dead.”

Chad McCabe of Magdalena checks out a piece of wreckage. Very little of the plane remains on the mountain after 64 years.

Four others had been thrown out into the snow and brush, and it took until the following day to locate all but one.

“We never could find the ninth. So we hunted, I guess two hours,” he said. “During all that, I noticed a black box laying out there on the bluff. It was about a maybe a 30- or 40-foot drop right straight off, and this thing was laying right on the edge of the bluff.

“I got off my horse, and everybody was looking around there, and I walked over and picked this thing up. It was just a black square box. It had a pair of view glasses,” he said. “I was fiddling with it. One of these MPs run over there and said, ‘Hey kid, you can’t have that,’ and he took it away from me, and I said, ‘What is it?’ And he said, ‘I can’t tell you.’ I found out it was one of those Nordon top secret bombsights. That’s all they cared about.”

The ninth crewman was eventually found, and by chance, Tom said.

“I just happened to wander around the hill about a hundred feet, and there was a prospector hole 10 feet deep somebody had dug years before. This guy had fallen into that hole. So they went and got a rope off a saddle and pulled him out. Wrapped him up and tied him on the horses, and then we led the horses back to where they had these ambulances parked down there about two miles down.”

He said the major in charge “had a whole bunch of soldiers the first day. But we didn’t see them anymore. I don’t know why all the GIs hid from him.”

The Kellys didn’t make it back home until the afternoon and warmed up with a bottle of whiskey Tom’s uncle liberated from the coat pocket of the major.

“He had one of these big old army overcoats on. You know, the old olive green overcoats. Wool. And in the coat in the right-hand pocket he had a bottle of whiskey sticking out,” he said. “So you how the ol’ cowboys are. Uncle Jim, well, he was looking at this bottle of whiskey, and he waited till this major turned around to give all these orders, and Uncle Jim just rode by and took his whiskey. So when we got home, my dad cooked a great big dinner. It was about three o’clock in the afternoon, and everybody was feeling pretty good with the major’s bottle of whiskey.

“We had some letters from some of their relations,” Tom said. “Got two or three letters from some of them. Thanking us for what we did.”

Although those young men of the Army Air Corps in their Flying Fortress never saw one day in actual combat, they were ready, willing, and most likely eager to join the fight in the skies over Europe.

They and all too many more deserve your salute on Memorial Day. Keep them all in your thoughts at the ceremony at Isidro Baca Park this Monday.