On July 16, 1945, at 5:29:45 a.m. the sky over Socorro County turned red and a mushroom cloud appeared in the distance to the southeast. Little did residents know that for the first time in history the atom was split, sending searing heat across the desert and knocking observers to the ground at what was then known as White Sands Proving Ground.

Seventy-seven years later there is practically no trace of that blast to be seen, except for a crumbled concrete footing of the 100-foot tower – constructed from a surplus Forest Service fire watchtower – from which the “gadget” was detonated.

On Saturday, Apr. 2, the general public will be allowed to enter White Sands Missile Range to visit Trinity’s ground zero.

A release from White Sands Missile Range stated that due to changes in circumstances surrounding COVID-19 restrictions, proof of vaccination and reservations are not required to tour the Trinity Site.

This is a free event. The Stallion Gate is open from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. Visitors arriving at the gate between those hours will be allowed to drive unescorted the 17 miles to Trinity Site. The road is paved and marked. The site closes promptly at 3:30 p.m.

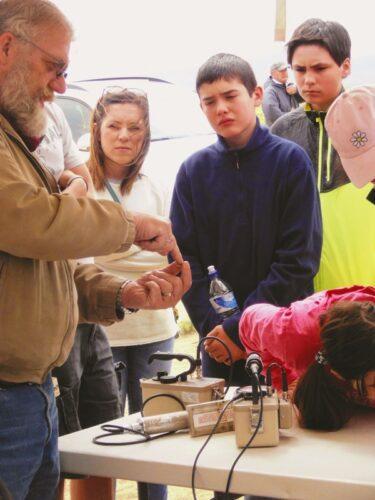

Visitors learn about Geiger counters and radiation levels at Ground Zero.

John Larson | El Defensor Chieftain

At the site visitors can take a quarter-mile walk to ground zero where a small obelisk marks the exact spot where the bomb was detonated. Historical photos are mounted on the fence surrounding the area. Visitors can also ride a missile range shuttle bus two miles from ground zero to the Schmidt/McDonald Ranch House. The ranch house is where Manhattan Project scientists assembled the plutonium core of the bomb.

Life was a bit out of the ordinary for those in San Antonio during that period. In a 2012 interview, Lucille Catherine Miera said she remembered military men in and around the community.

“There were other men, too. Not military,” she said. “I met many of them and was told later that Oppenheimer was there. I may have met him, but I was only 13 at the time, so I’m not sure.”

She said the men were gone during the day and came back at night.

“No one said where they worked other than they were just working on a project,” she said.

Lucille remembers overhearing some of the GI’s talking on the telephone.

“They said they were talking to their girlfriends. ‘Oh, I’ve got to call Mary Ann,’ they would say,” she said. “But the things they were saying didn’t sound like it. They were saying things like how many of this or that, and what are the times, something you wouldn’t expect someone to talk to their girlfriend about.

“Then they would say I’ve got to call my other girlfriend, so-and-so,” she said. “We figured they were using some kind of code. Or they had lots of girlfriends!”

She said her grandfather had rented out cabins for the servicemen and government people, and there were also trailers and army tents in the vicinity.

“Friday night was always movie night at their recreation area, and all the soldiers were there like usual, eating popcorn,” she said. “Saturday was normal, but Sunday was quiet.”

“We had a flashlight, and my grandmother would sometimes wake me up by shining it in my face,” she said. “That Monday morning I woke up because of a bright light, and I said, ‘Turn it off, Grandma,’ but she wasn’t there and there was no flashlight. The whole room was lit up. I didn’t know what was happening.”

She said her grandmother came into the room and told her to stay inside. “But I went outside to see anyway,” she said. “Everything was really bright, like a halogen lamp. The little trailers and tents were all gone.”

The site of the blast was closed to the public for a few years following World War II, and it wasn’t until September 1953 that about 650 people were able to visit ground zero at the first Trinity Site Open House.

A small group from Tularosa visited the site a few years later on the anniversary of the explosion to conduct a religious service and prayers for peace. A similar visit was made on July 16, 2009, when seven Buddhist monks made a trek to WSMR Stallion Gate to conduct a 24-hour silent vigil on the anniversary of the detonation of the world’s first atomic bomb. The spiritual pilgrims began their walk at Los Alamos National Laboratory and along their route, the walkers stop to educate those interested in the effects on humans from nuclear weapons, using photographs and data from the bombing of Nagasaki.

Although radiation levels are low, some feel any extra exposure should be avoided. The decision is yours. It should be noted that small children and pregnant women are potentially more at risk than the rest of the population and are generally considered groups who should only receive exposure in conjunction with medical diagnosis and treatment.

The simplest way to get to Trinity Site is to enter White Sands Missile Range through its Stallion Range Center gate five miles south of U.S. Highway 380. The turnoff is 12 miles east of San Antonio.

Trinity Site is a national historic landmark.