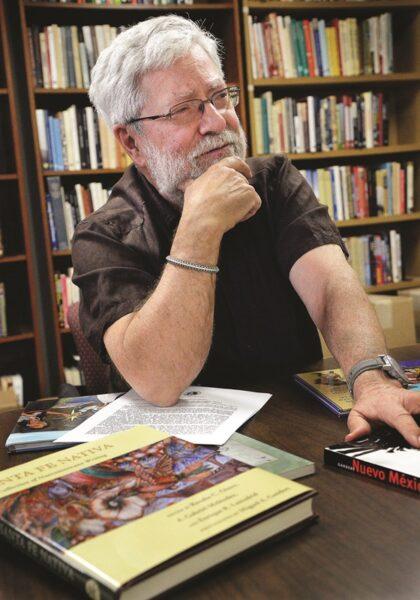

Professor Enrique R. Lamadrid will talk about the history

of New Mexico’s Genizaros this Saturday at Socorro Public Library.

Jim Thompson|Albuquerque Journal

Enrique R. Lamadrid, a celebrated University of New Mexico Professor Emeritus of Spanish and former director of Chicano Hispano Mexicano Studies, will present his extensive knowledge of New Mexico’s Genizaro culture at the annual membership meeting of Friends of El Camino Real Historic Trail Saturday, April 15, at Socorro Public Library.

In 2019, Lamadrid coedited the book Nación Genízara, Ethnogenesis, Place, and Identity in New Mexico with Moises Gonzales. He describes his expertise as “all the untold, forgotten stories.” The stories are basically family histories to many New Mexicans.

Genízaros were indigenous people who were taken, primarily as children, into Spanish colonists’ homes, supposedly “freed” after some time, having lost their own language and culture.

The term continued to be used into the 1900s to identify Plains Indian women and children captured in intertribal warfare and sold or ransomed to Spanish authorities who assigned them to Christian settlers for “civilizing” and service as domestics and herders.

Several Genízaro communities were established with the offer of free land between Belen and areas further north to serve as barriers between the nomadic tribes and the Spanish colonies.

Lamadrid said the very first Genízaro land grant approved was Belen.

“By the early 1800s, a community across the river from Santa Fe was a Genízaro hangout, a hangout for free Genízaros. People in Santa Fe complained to the authorities about them, saying they were unemployed and didn’t want to work,” he said. “They don’t want to work anymore because all of them had worked for free for years and years as weavers or shepherds or domestics or as agricultural workers, and they were not interested in working any longer for anybody else but themselves, but they had no land.

“But they were free at that point,” he said. “You could only be held as a slave until you paid off the ransom that your master may have traded you for in one of those big trade fairs like in Pecos or Taos they had.”

The governor at the time, Tomas Velez Gachupin, helped authorize land grants for the Genízaros.

“That’s the story of Belen,” Lamadrid said. “It was a bunch of Genízaros that first founded Belen.”

From the 1740s to the 1790s, other communities such as Abiquiu, Las Trampas, San Miguel del Vado, Ojo Caliente, and San Miguel de Carnué were established as Genízaro buffer settlements.

Even today, the Genízaro dance known as the captive dance is still danced in the Pueblo of Abiquiu on the Catholic feast day of Santo Tomas.

Sheri Armijo, a Friends of El Camino Real Historic Trail member, said she learned about the Genízaro lineage in her family from her parents and grandparents.

“People say, ‘What happened to the Genízaros?’ I say, ‘Here I am!’” she said, “I have it on both sides. We were basically absorbed into the Hispanic culture. My mother remembers that her dad would talk about some people in town that are traces of it.”

She said she understood that by 1776, fully one-third of the New Mexico population were Genizaros.

“The church encouraged it because these Native people, they had to be Christianized,” Armijo said. “That was part of the bargain. You were allowed to have them but had to have them baptized. You had to make them part of your household, and a lot of times, they would marry into their master’s family.”

She explained what her father and grandfather told her about the difference between a Genizaro and a slave.

“The difference was that people weren’t set to be a Genizaro for their whole life,” Armijo said. “You could marry into an upper class, or you could pay off the price your master paid for you. You could go from being a servant one year to becoming a landowner. It was not just a racial thing, but class. But since then, people just wanted to kind of forget their roots because of the negativeness. Kind of like an unspoken rule.”

Lamadrid’s talk this Saturday will start at 1 p.m. in the Alice Kase Room upstairs at Socorro Public Library and will be followed by a Q&A session.

“People in central New Mexico are discovering they are part of this heritage,” Lamadrid said.

Besides Nación Genízara, Lamadrid’s other books include Amadito and the Hero Children, a bilingual children’s book about influenza epidemics in New Mexico, and Nuevo México Profundo: Rituals of an Indo-Hispano Homeland, in which he collaborated with photographer Miguel Gandert to document the rituals of people of indigenous and Spanish descent in New Mexico.

Lamadrid’s teaching and research interests include Southwest Hispanic and Latin American folklore and folk music, Chicano literature, and literary recovery projects. He has done fieldwork with students all over New Mexico and in Mexico, Spain, Colombia and Ecuador.

He also served as a field worker and presenter for the Smithsonian Institution’s Festivals of American Folk Life and has done extensive work for the Museum of New Mexico and the National Hispanic Cultural Center.

As an academic curator, he has worked with numerous exhibits with his students and headed the design team for the Camino Real International Heritage Center.