A replica of Fat Boy, the bomb detonated over Hiroshima, is displayed at ground zero.

John Larson | El Defensor Chieftain photos

On July 16, 1945, at 5:29:45 a.m. the sky over Socorro County turned red and a mushroom cloud appeared in the distance to the southeast. Little did residents know that history’s first nuclear weapon was being tested on former ranchland south of Bingham, at what was then known as White Sands Proving Ground.

On Oct. 15, the Trinity Site Open House will once again allow visitors to have an up-close look at Ground Zero as well as the ranch house appropriated by the U.S. Army where Manhattan Project scientists assembled the bomb.

Several people in Socorro and the county still remember that morning as well as the military activity in San Antonio before and after the test.

Although hostilities in Europe ended in May with the defeat of the German army, the United States was still at war with Japan, and it was not unusual to see a military presence in the area.

The atomic blast that morning is etched into the memories of San Antonio and Bingham residents and many had spoken of their memories over the years.

One told of a sizable military presence in San Antonio in the weeks preceding the test. Another spoke of being awakened at 5:30 a.m. and thinking it might be a bombing by Japanese air forces.

One remembered farm animals being sick afterward and some cows losing their hair.

The late Holm Bursum III recalled that a rancher in Bingham had a black cat whose hair was turned white on one side and he sold it to a tourist for $5.

Seventy-seven years later there is practically no trace of that blast to be seen, except for a crumbled concrete footing of the 100-foot tower — constructed from a surplus Forest Service fire watch tower — from which the bomb was detonated. The large stone and mortar monument is just about all there is to see.

Saturday, Oct. 15, the general public will be allowed to enter White Sands Missile Range to visit Trinity’s ground zero.

Although the site of the blast was closed to the public for a few years following World War II, in September 1953 about 650 people attended the first Trinity Site open house.

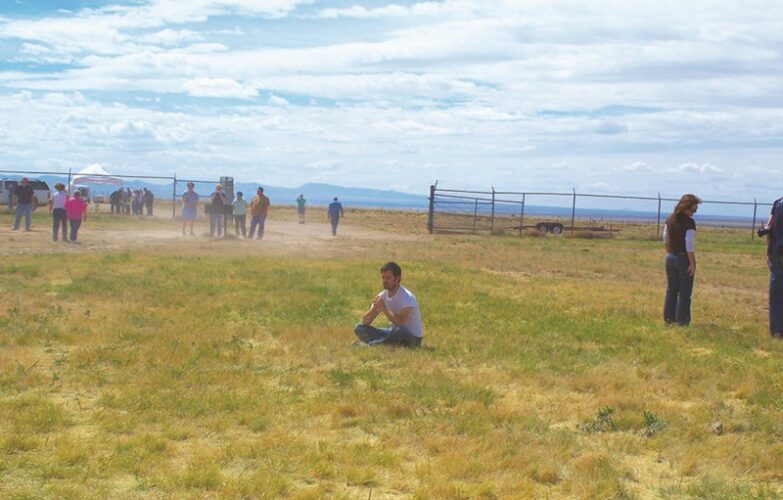

Visitors come to Trinity Site for different reasons

A small group from Tularosa visited the site a few years later on the anniversary of the detonation to conduct a religious service and prayers for peace. Similar visits were made annually in recent years on the first Saturday in October, and a second Open House was scheduled on the first Saturday in April.

The 51,500-acre area was declared a national historic landmark in 1975. The landmark includes ground zero where the bomb exploded; the base camp where scientists and support staff were housed; the remains of one of the tower columns; and the Schmidt/McDonald ranch house south of the site where the core of the bomb was assembled.

In addition, one of the old instrumentation bunkers is still visible beside the road just west of ground zero.

Visitors to the April and October open houses at the site have steadily grown over the past dozen years and a turnout of over 5,000 participants is not unusual.

Although no record is kept of where attendees come from, license plates in the sprawling parking lot accounted for dozens of states. That’s not to mention the countless visitors from different counties, curious about the Manhattan Project and seeing the birth of the nuclear era.

The open house is free, and no reservations are required.

At the site visitors can take a quarter-mile walk to ground zero where a small obelisk marks the exact spot where the bomb was detonated. Historical photos are mounted on the fence surrounding the area.

While at the site, visitors can also ride a missile range shuttle bus two miles from ground zero to the Schmidt/McDonald Ranch House. The ranch house is where the scientists assembled the plutonium core of the bomb.

The explosion, only two miles away, did not significantly damage the house. Most of the windows were blown out, but the main structure was intact.

Years of rainwater dripping through holes in the roof did much more damage. The barn did not do as well.

During the Trinity test, the roof was bowed inward and some of the roofing was blown away. The roof has since collapsed.

In 1984, efforts began at making the house appear as it did on July 12, 1945, allowing visitors to experience what life was like for a ranch family in the early 1940s.

Although radiation levels are low, some feel any extra exposure should be avoided.

It should be noted that small children and pregnant women are potentially more at risk than the rest of the population and are generally considered groups who should only receive exposure in conjunction with medical diagnosis and treatment.

Typical radiation exposures for Americans per the American Nuclear Society:

- One hour at Trinity Site ground zero – one half mrem;

- Cosmic rays from space – 47 mrem at Denver per year, 28 mrem at St. Louis;

- Radioactive minerals in rocks and soil – 63 mrems per year on Colorado Plateau;

- Radioactivity from air, water and food – about 240 mrem per year;

- About six mrem per chest X-ray, 65 mrem per hip X-ray and 110 mrem for a CAT Scan;

- Watching television – less than one mrem per year;

- Wearing a plutonium-powered pacemaker – 100 mrem per year.

The simplest way to get to Trinity Site is to enter White Sands Missile Range through its Stallion Range Center gate.

Stallion gate is 5 miles south of Highway 380. The turnoff is 12 miles east of San Antonio.

The Stallion Gate is open from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. Visitors arriving at the gate between those hours will be allowed to drive unescorted the 17 miles to Trinity Site.

The road is paved and marked.

The site closes promptly at 3:30 p.m. Visitors must have a REAL ID card, passport, or military ID to enter.